The Generosity of a Plant to Drop Its Leaves: An Exercise in Curating Decay

Lena Johanna Reisner with contributions by Anaïs Senli

Silo – Arte e Latitute Rural

Serrinha do Alambari (BR)

Part of the final presentation of the residency program Resilience: Artist in Residence

Plants are generous in how they give away both their ripe fruits as well as their brown leaves. The concept of this as a generous act is based on the importance of edible fruits for human and more-than-human cultures. Seen from the perspective of plants which are growing these fruits, they serve as valuable containers for seeds that facilitate their natural reproduction. Brown leaves in comparison appear to be a rather modest offering. They are nothing but leftovers in a dynamic process of growth and renewal or the signs of a struggle. Once they fall onto the ground and decompose, however, they become part of a vital, giving process and – over time – transform into soil.

The curatorial exercise and site specific installation The Generosity of a Plant to Drop Its Leaves consisted of leaves of banana trees, palm trees, bromelia and fern arranged on discarded bedsteads and furniture found in the abandoned Top Club building in Serrinha do Alambari. With the leaves decomposing and the building in disrepair, the work alluded to different forms of decay, materiality and reproductive cycles. Carrying fallen leaves from a living ecosystem into a human housing, i.e. a temporary exhibtion space, the work likewise negotiates the relationship of outdoors and indoors. Like a ritual, bedding down the foliage translates as an act of care and creates a link between the shape of leaves to the physiognomy of human bodies as well as the material cultures they inhabit.

The text Reading Among Messy Symbionts came out of an extended period of reading and a series of excursions during the three weeks residency period, as well as conversations with fellow participants and the Berlin-based artist Anaïs Senli.

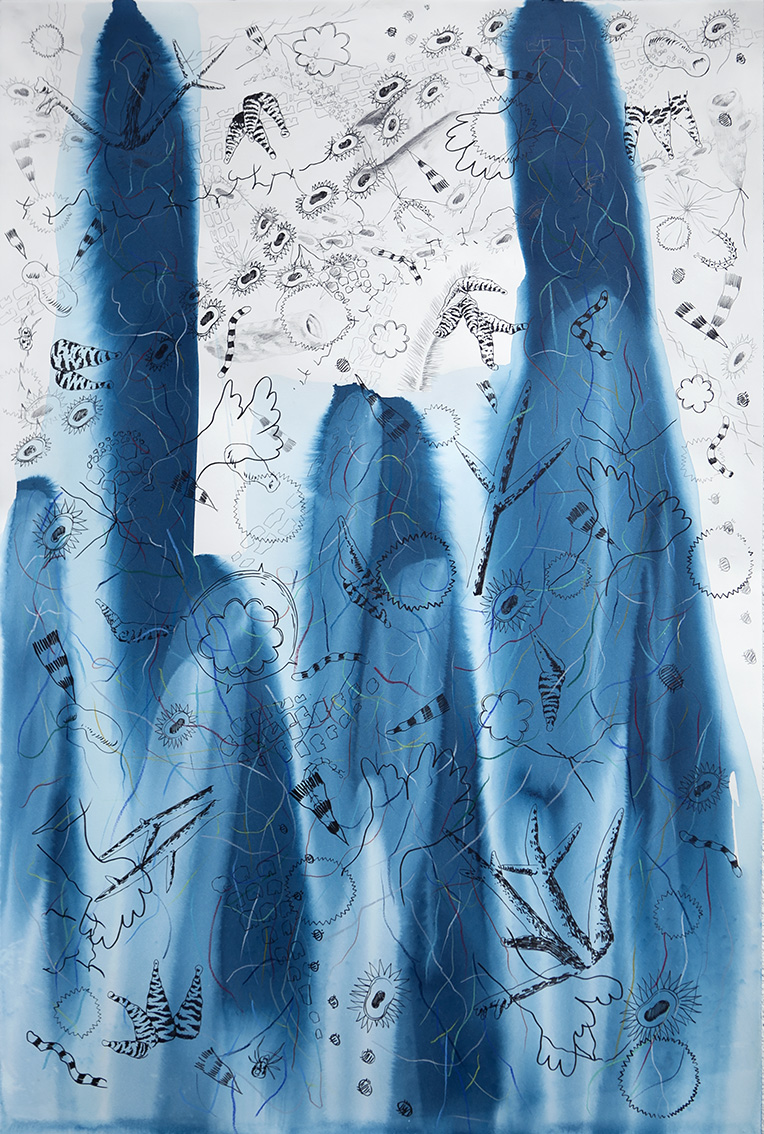

Anaïs Senli, Filamentous growth of cells in a slimaway 2, 2018, caligraphic pen, pencil, ink, 120x80cm, Courtesy the artist

Reading Among Messy Symbionts

Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble undoubtedly is a productive read for a stay at Itatiaia National Park. The so called multi-species everything, this messy, muddy, and chthonic constellation finds perfect expression in the mountain region, all covered with trees, shrubs, rocks and countless other critters. Imagine you were a tree, hosting a couple of Bromelia on your branches, these ubiquitous epiphytes, that never root in the ground but derive their moisture and nutrients from air and rainwater. They allow for another micro-ecosystem to take place in their crown and leaves, seedlings growing on debris, insects. You might have one of those plants who like to climb and hang sit comfortably in a fork. With their tentacular feelers they are always looking out for something to grasp, while exposing their greenish organs to the sunlight. Ferns reproduce via spores, without seeds or flowers and spread their beardy leaves over all kind of surfaces. You might entertain a close relationship with green or black moss, a red microfungus or different sorts of lichen, some of which form colourful spots, whereas others grow like a multiple-branched tuft, like the airway of a respiratory system or a leafless mini-shrub. In the uncontaminated air of the nature reserve these sensitive creatures seem to cover entire areas, developing over years until they reach a remarkable size like those along the road. It is through engaging with every single constituent of the forest and the shrubby landscape of Itatiaia, through my botanic interest, that I come to a deeper understanding of this thick and humid, lush and flourishing reality. It is a remarkable ecosystem. I want to call it an organism.

While reading a bug lands on the reproduction of Endosymbiosis:

Homage to Lynn Margulis and makes my story.1 Symbiosis means the coexistence of beings of different kind or in other words: a system of living organisms that exist in close physical contact. The roots of maple or oak trees for example are closely tied with up to 300 different sorts of symbiont fungi some of which are known as mycorrhiza. The beautiful lichen of Itatiaia National Park are organisms comprised of fungi, algae and cyanobacteria. Evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis posited, that evolution on a cellular level occurs through the symbiosis of bacteria of different origin and with different abilities rather than through random mutations. Her theory draws attention to mutually beneficial forms of collaboration between organisms, while at the same time altering the concept of what constitutes a subject. “Like kefir,2 we and all other organisms made of nucleated cells, from amobae to whales, we are not only individuals, we are aggregates. Individuality arises from aggregation, communities whose members fuse and become bounded by materials of their own making.”3 Donna Haraway moves in a similar direction when speaking of a “subject- and object-shaping dance of encounters”4 where species of all kinds occur: “To be one is always to become with many.”5

Surroundings of Top Club in Serrinha do Alambari

While moving in the forest I become part of its organism. I might use repellent to protect myself from mosquitos and other critters wanting to feed on my skin. I might not drop all those civilisational features and habits that define my self-understanding as coming from a history of binary separation. Nevertheless I am being sucked up by a continuous movement, which can be described as breathing, a vital function strongly associated with the spiritual realm.6 With its symbiotic entanglements and organic networks life breathes in the sappy ecosystem of the forest and its surroundings, where everything that dies, decays with dignity to serve as compost for life’s ongoingness, its constant vibration.

The forest is ongoing. It does not disappear, when I stop to think or perceive it. Since I was old enough to understand life as something independent from my mental configurations, of my very presence in this world, I’ve wondered, what the forest does at night, once it becomes inhospitable for me, this white, Western human being, that I have always been. While I was sitting at home in the evening, my imagination was still with the forest, with the chthonic ones, my love still with this organism, my breath still in sync, my longing and my desire to embrace still with the forest, and sometimes with the sea, when my parents had brought me there, still buried in the sand, my imagination still hoping to merge with the horizon I had stared at for the hottest hours of the day. What if becoming with, this state of being in inter- and intra-action, transforms into a state of becoming one, an experience of oneness, blissfully tickling. What if an aggregation of organisms, a human being, originating from a subject- and object-shaping dance of encounters becomes a symbiont in itself, that is, the smaller of two entities involved in a moment of symbiosis? Would this be a spiritual experience or a sensual, mystical?

Look outside a window of Top Club's first floor in Serrinha do Alambari, phtoto: Mariana Lage

I like to think of Etel Adnan’s series of paintings of Mount Tamalpaïs, a peak in California, with which she grew familiar once she moved to San Francisco and later on to Sausalito. What became an attachment to Mount Tamalpaïs transformed into a passion that would overflow not only her artistic mind but her entire life.7 “Year after year coming down Grand Avenue in San Rafael, coming up from Monterey or Carmel, coming from the north and the Mendocino Coast, Tamalpaïs appeared as a constant point of reference, the way a desert traveler will see an oasis not only for water, but as the very idea of home. In such cases geographic spots become spiritual concepts.”8 Etel Adnan’s stories of manifold excursions to her favourite landscape, but also my own experiences as recounted above, might not escape the suspicion of an edenic narrative, that is assuming the possibility of or an initial state of harmony “in which human beings live as one with other divine creations.”9 There is a soft echo of back-to-the-wild ideas that continue to resonate with the Western imaginary. However, one shouldn’t underestimate the existential urgency of Etel Adnan’s commitment to the mountain. Her relationship with Mount Tamalpaïs resembles an addiction. She speaks of love, which is not benign, because “no love is benign. It can and it does engage one’s whole being.”10 – “For years I am going, coming back, turning around the mountain, getting up in the middle of the night to make sure it is still there, staring at it, walking all over it, and dreaming, dreaming…”11

While the fog closes in on us, the rain continues to drum on the roof I’m dreaming, too, of the high standing grass between the mossy rocks moving in the wind, tiny little frogs with red bellies, soil soaked with water and its thick, savoury smell. I’m dreaming of configurations of biota, the chthonic ones inhabiting Terrapolis, an underground network of mycorrhiza and fungi moving minerals and other carriers of information through the soil – and I’m moving with them. How does it feel to be among those microbial communities that perform symbiogenesis, build cells and aggregations of increasing complexity, the fungi and bacteria of decay, decomposing a dead leave and engaging in metabolism’s set of life sustaining chemical reactions? “In death the self dissolves. But life in a different form goes on:”12 the microscopic dances of the smallest entities rubbing against each other, eating and feeding on each other, fusing and reproducing without sexual partner, some of them escaping programmed death. All these caretakers of life and decay, I guess, to some extend, they love each other.

Itatiaia National Park, Serrinha do Alambari,

27 February to 9 March, 2018.

- Shoshanah Dubiner’s Endosymbiosis: Homage to Lynn Margulis, 2012, is one of two coloured reproductions in Donna Haraway: Staying with the Trouble, 2016, p.59.

- Kefir is a fermented milk drink from the Caucasian mountains containing populations of live microbes.

- Lynn Margulis: Kefir and Death, in: Lynn Margulis & Dorion Sagan: Slanted Truths, 1997, p.89.

- Donna Haraway: When Species Meet, 2008, p.4.

- Ibid.

- See Lena Johanna Reisner on Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s Third Lung for the eponymous exhibition at Galerie im Turm 2018.

- Etel Adnan: The Costs for Love We Are Not Willing to Pay. 100 Notes – 100 Thoughts, No:006: Etel Adnan, 2011, p.5f.

- Etel Adnan: Journey to Mount Tamalpaïs, 1986, p.10.

- Candace Slater: Amazonia as Edenic Narrative, in: William Cronon (ed.): Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, 1996, p.115. Italics by the author.

- Etel Adnan: The Costs for Love We Are Not Willing to Pay. 100 Notes – 100 Thoughts, No:006: Etel Adnan, 2011, p.6.

- Etel Adnan: Journey to Mount Tamalpaïs, 1986, p.11.

- Lynn Margulis: Kefir and Death, in: Lynn Margulis & Dorion Sagan: Slanted Truths, 1997, p.84.