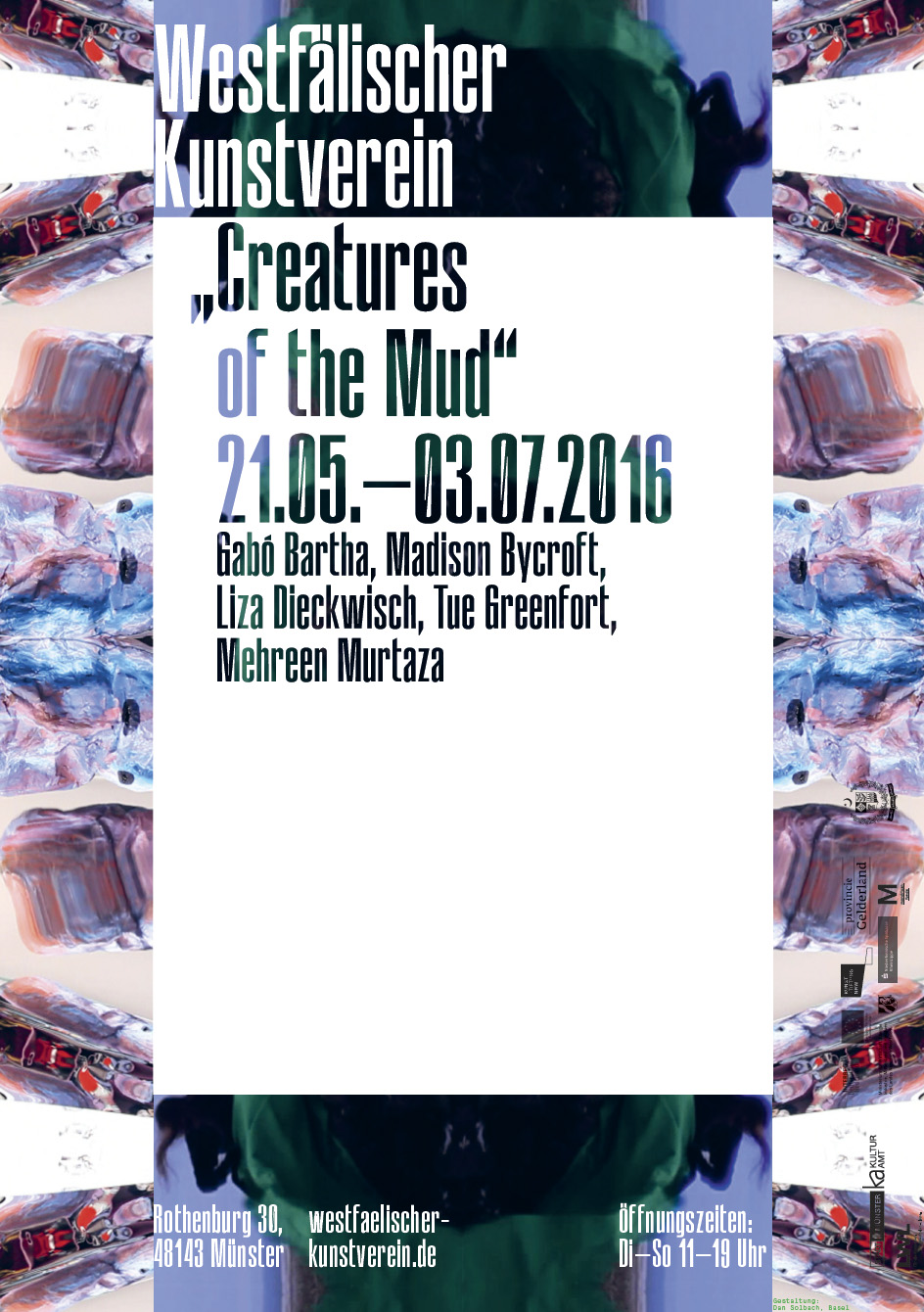

Creatures of the Mud

Gabó Bartha, Madison Bycroft, Liza Dieckwisch, Tue Greenfort, Mehreen Murtaza

May 21 – Jul 3, 2016

Westfälischer Kunstverein

curated by Lena Johanna Reisner

The phrase Creatures of the Mud has something monstrous about it, indeed, there is nothing especially cuddly about the ‘ecological thought’ as Timothy Morton describes it: “The ecological thought imagines interconnectedness which I call the mesh.”1 This “mesh” is nothing less than the interconnectedness of absolutely all living and non-living entities on Planet Earth and much, much further afield. It is a powerful construct without a clear beginning or end, devoid of linearity or clusters of sub-groups in line with an evolutionary scheme. The logic of the mesh decrees that each point is equally at the centre and the periphery of a system.

“I’m a creature of the mud, not the sky.”2 This statement by the biologist and historian of science, Donna J. Haraway, contains a number of aspects that could be considered paradigmatic for an ecological or worldly philosophy. The orientation towards “mud” at once affirms the viscerality and materiality of individual existence, as well as situating human existence within the context of Earth as a whole and the inter-actions and intra-actions with other species. At the same time, this reference is a liberation from a tradition in European philosophy in which – according to René Descartes – the dualisms of body and spirit, self and the world are thought of as separate entities. “To be one is always to become with many,”3 effectively means that subjectivity, identity and, even more fundamentally, vitality do not arise in opposition to one another, but in a process of ongoing, renewed mutual becoming. The fact that mud or viscerality isn’t a simple figure as such, but a highly complex reality, emerges from Haraway’s analysis and her fascination for genomes, bacteria, fungi, symbionts and all manner of species with whom we share this world.

The works of the artists featured in the exhibition Creatures of the Mud resonate with these ideas and probe the consequences of this insight in a variety of ways. For example, our relationships with other species are approached on an extremely direct level as well as the forms of interdependence that arise from such interconnectedness and the responsibilities it implies. Far from being that mysterious ‘other’, the ‘monstrous’ turns out to be a simply incomprehensible constellation of being of which we are part and which demands both our subjectivity as well as our sensibility.

One of the exhibition’s themes centres on the way in which we generate and preserve knowledge by means of scientific, speculative, mythical, aesthetic, research-based and discursive processes. In her treatise on Agential Realism, theoretical physicist Karen Barad proposes the close interconnectedness of being and knowledge. The production of knowledge doesn’t merely generate facts; the practices of knowledge production should rather be understood as “material entanglements” that cooperate in the permanent configuration and reconfiguration of the world.4 Thinking, theorising and observing are thus less modes of description and more forms of intra-action in the midst of and as part of the world.5 Against this backdrop, the question regarding our responsibilities for our agencies operates on a wholly new level. It opens up a vista upon a terrain of possibility and opportunity geared towards resituating ourselves in this extraordinarily dynamic and lively network which “we” undoubtedly share with other agents.

The arrangement of the artistic elements in Creatures of the Mud is motivated by the idea of an ecology and interaction in the exhibition space, in which the narratives being related and the sensibilities they generate, form a mutual cosmos. The space is thus populated by all manner of entities, such as fictional figures, mythical forms, bacteria, marine organisms, synthetic materials, insects, vegetables, as well as living individuals in the truest sense of the word.

- Timothy Morton, The Ecological Thought (Cambridge, 2010), p. 15.

- Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis, 2008), p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- See Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (London 2007), p. 91.

- Ibid., p. 90.

Mehreen Murtaza

For her installation … how will you conduct yourself in the company of trees, Mehreen Murtaza has made use of the amplylit foyer in which she has placed plants from the University of Münster’s Botanical Garden. Ivy, cacti, palm trees, oleanders and other shrubs have been hooked up to a computer by a series of leads as though part of a scientific experiment. The apparatus is a simple construction for measuring low voltage electrical activity on a cellular level.

For a long time, the limited ability for plants to move or to react to stimuli was associated with an overall deficit in sensory perception. Touch me nots, vines and carnivorous plants – so-called sensitive, reactive plants – were considered to be exceptions to the rule. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, these plants began to arouse interest among a growing number of scientists. Experiments conducted upon plants of this kind showed that electro-physiological signal processing not only takes place in animal cells, but in plant cells, too. Not until the nineteen sixties did it become clear that ordinary plants also showed action-potential thereby fundamentally casting doubt on the received assumptions regarding sensory perception in plant life per se.

Plant neurobiology as a separate discipline has been gathering momentum since the beginning of this century and is predicated upon further analogies between plant life and animals, for example, the connection between nerve-like structures in plants. The possibility of a form of intelligence has also been investigated, though the subject continues to be controversial among plant physiologists. During the nineteen sixties, experiments investigating electro-physiological signal processing and reactivity were at times also interpreted as parapsychological phenomena and gave rise to speculation about cellular awareness that connects all living organisms. Although experiments of this kind have stimulated increased curiosity and openness about, as well as respect for living organisms in general, they have also meant that plant neurobiology has been burdened with the stigma of esotericism.

… how will you conduct yourself in the company of trees tells a story of living matter and also the relationship between so-called qualified and unqualified scientific knowledge. Furthermore, its narrative encompasses science when it engages with that very space in which thinking about our world can only occur as a kind of speculation. Nevertheless, the function of … how will you conduct yourself in the company of trees is not merely metaphorical; inasmuch as the measurement of electrical impulses and activity is not expressed as actual values but is interpreted musically instead, a different form of aesthetic experience is made possible. It is not so much about the intellectual feat of abstraction in interpreting the values themselves but more about an immediate form of communication via acoustic signals, as well as how we behave when plants respond to our presence and actions with sounds and music.

MEHREEN MURTAZA,… how will you conduct yourself in the company of trees, 2015-16, TUE GREENFORT, Aasee Water Filtration, 2007, exhibition view Westfälischer Kunstverein 2016, photo: Thorsten Arendt

MEHREEN MURTAZA, … how will you conduct yourself in the company of trees, 2015-16, detail, exhibition view Westfälischer Kunstverein, photo: Thorsten Arendt

MADISON BYCROFT, Chthonigoegigoog, 2016, detail, Courtesy the artist

Madison Bycroft

Madison Bycroft’s Rag of Cloth: Ode to the Vampire Squid is inspired by H. P. Lovecraft’s short story The Call of Cthulhu which was written in 1928. The story is narrated by the great nephew of a recently deceased emeritus professor of Semitic languages; in his role as his great uncle’s heir and executor, the young and diligent anthropologist examines the late professor’s papers and pieces together the whole horrifying truth of the myth surrounding the Cthulhu, an extraterrestrial entity venerated by a few widely dispersed groups and secret cults. Not unlike the Cthulhu, Madison Bycroft’s “Vampire Squid” is a fictional figure, despite being modelled on the eponymous vampire squid, a species of deep-sea cephalopod. Embodied and performed by the artist, the vampire squid feeds on words; the kind of words we use to try to describe the monstrous, to structure our world, to differentiate and to create hierarchies. “Chthonic” means “in, under or beneath the earth” but also “subterranean”. Madison Bycroft’s Chthonigoegigoog operates with this lexical root and presents artefacts which are to be understood as suggestions or theories.

In one arrangement of objects Madison Bycroft cites the Bunyip, a creature referenced by many Indigenous Australian peoples, that dwelled in swamps, billabongs, riverbeds, creeks and water holes. When British settlers began to describe and classify the flora and fauna of Australia they followed a standardised and scientific procedure that privileged only what they saw. Singular, white, colonial vision and epistemologies formed the basis of a knowledge with an ontological hierarchy that discredited anything outside of that. How might we imagine or decolonise our imaginary in regards to the unsaid, unseen creature? Using her Taxonomy Table the artist attempts a different form of classification. Fragments of text have been written in chalk on a black, stage-like platform. Sculptural elements made from clay sit on and around the platform and are connected diversely by ropes, tubes, rods, pipes and ducts provoking thoughts about an overarching ecological principle of the interconnectedness of all being. Ultimately, Madison Bycroft’s Proposal for the Ineffable lends the Bunyip and the indescribable in general one of many possible countenances.

A series of sculptures, some of which are mobile, invite one to move them around in the gallery space. Lines can be understood as a philosophical and at the same time a performative, spatial exercise geared towards describing boundaries and, quite literally, the drawing of lines. Based on Karen Barad’s ideas, they presuppose a dynamic world in which differentiations always ever exist as a possibility. Furthermore, Fulcrum contemplates the condition of being wrapped in and by something. An oyster, for example, forms a pearl by coating a microscopic foreign body that has inadvertently entered the organism in layers of nacre.

Liza Dieckwisch

Liza Dieckwisch’s works for Creatures of the Mud are more closely aligned to the mud in the exhibition’s title than to the creatures. Material in origin, they suggest a synthetic organic life form in their structure and arrangement. Liza Dieckwisch’s compositions seem to feed upon a shared body out of which clear pictures emerge from time to time, only to be reabsorbed and fashioned into something new. This takes place in the form of an object resembling compost, in which fragments of sketch-like experiments and relics from earlier works embark upon a further phase of their cycle.

Alongside her activities as a visual artist, Dieckwisch experiments with terse lyrical statements. Her large-format work in the main hall is linked to a poem dealing with a possibility for conserving jellyfish. During this process, the fluid is removed from these water-filled cnidarians and replaced with synthetic material. The expansive work comprising different silicons conveys a sense or feeling of this material, taking on the appearance of an ambivalent and in parts, shimmering mass of slime.

The sequinned material provides a similarly ambivalent surface with a capacity to reflect light. A photograph of some bread dough conceals its true identity at first. Endowed with interstellar or planetary associations, the billowing dough with its bulging amplitude reveals itself by virtue of its characteristic adhesive property, in this instance by sticking to a glass bowl.

LIZA DIECKWISCH, Digitaldruck, 2016, Courtesy the artist

GABÓ BARTHA, Untitled (excerpts of an archive), 2010-16, frame, Courtesy the artist

GABÓ BARTHA, Untitled (excerpts of an archive), 2010-16, frame, Courtesy the artist

Gabó Bartha

Gabó Bartha’s contribution likewise introduces an earthy and ‘earthing’ dimension to the exhibition. As an art historian and a biodiversity activist, Gabó Bartha has been organising events and actions that intersect with visual art for a considerable time. A series of photographs from her archive depict foodstuffs from the wine region Tokaj in Hungary. Almost like a series of notes, the photographs on show document a conference on the topic of seeds, as well as pictures of artisan markets, seed-swap events, photographs of different and partly old varieties of fruit and vegetables. An important topic in the selection of the photographs is a garden in Mád, Tokaj, that Bartha set up in 2011 as a kitchen garden for the ostensible purpose of self-sufficiency. Irrespective of their utility value, the plants in this garden were allowed to live through all the phases of their cycle. In this deregulated scheme of things, the existence and coexistence of the plants seemed to be more dignified than in other imaginable contexts. Large numbers of photographs document the encounter with diverse life forms in this garden and are clearly motivated by curiosity and wonderment, as well as by an interest in research and an aesthetic impulse.

Gabó Bartha often presents her photographs when giving talks. Each image represents an individual story about political and social entanglements, about biodiversity, as well as a gardening practice residing somewhere between permaculture, biodynamic and organic farming. The loose sequence of images projected in the exhibition space take on a poetic dimension which, in turn, guarantees an insight into a way of living and unceasing research into our relationship to food and its production.

Tue Greenfort

In a similar way to Gabó Bartha’s work, Tue Greenfort’s Aasee Water Filtration focuses upon a local phenomenon and at the same time it situates the exhibition in the context of the city. Aasee Water Filtration is one of the annual editions issued by the Westfälischer Kunstverein from 2007 deriving from Greenfort’s participation in the fourth edition of the Sculpture Projects that year. In the context of the exhibition, Greenfort focused on the pollution of the Aasee due to the growth of blue algae. The bacteria produce poisonous cytotoxins that can cause allergic reactions in humans and if swallowed, can be extremely harmful to internal organs. The spread and proliferation of blue algae is promoted by a raised concentration of nutrients in the water. It is recognised that phosphates and nitrates used in intensively fertilized arable farming on an industrial scale run off into freshwater ecosystems. The thrust of the artist’s critique was as follows: in order to reduce the number of phosphates, EU-subsidised meat production and the highly intensified and industrialised agricultural production in the Münsterland region needed to be regulated. However, the causes of the problem weren’t addressed; instead, a cosmetic solution of sorts was arrived at by adding a substance called Iron (III)-Chloride to bind free phosphates chemically in the river and restrict the growth of the algae. The sculptural implementation of his investigations and his open critique of political processes involved in decision-making were accompanied by an edition with an almost painterly perspective. Aasee Water Filtration are paper filters bearing the traces of blue algae following the filtration process. They pose question of the current state of play ahead of the next Sculpture Projects Münster 2017.

TUE GREENFORT, Aasee Water Filtration, 2007, exhibition view Westfälischer Kunstverein 2016, photo: Thorsten Arendt

Credits

Texts: Lena Johanna Reisner

Translation: Tim Connell

Copy-editing: Jenni Henke

Design: Dan Solbach

Curator: Lena Johanna Reisner, guest curator plugin Schloss Ringenberg

Director: Kristina Scepanski

Coordination: Jenni Henke

Administration: Tono Dreßen

Assistant: Amelie Jörden

Installation: Anne Krönker, Bernhard Sicking, Robin Völkert, Lisa Wiemes

Gallery assistant: Bernhard Sicking

The artists, the curator and the team at Westfälischer Kunstverein would like to thank:

Dr. Markus Bertling, Stefan Bienas, Dr. Gudrun Bott, Erwin Dieckmann, Elke Gruhn, Jürgen Hausfeld, Tobias Haelke, Michael Heym, Dr. Philipp Kleinmichel, Dr. Eckhard Kluth, Gila Kolb, Joram Kraaijeveld, Bram Kuypers, Marcus Lütkemeyer, Margret and Dr. Hanns-Peter Reisner, Spedition Theodor Schulz GmbH und Co.KG, Samuel Treindl, Herbert Voigt, Elfi Weissig and Max Wigger as well as the Botanical Garden of the University of Münster for its loans.

Creatures of the Mud was part of the INTERREG VA project plugin, based at Schloss Ringenberg (schloss-ringenberg.de). Schloss Ringenberg offered stipends for artists and curators from Germany and The Netherlands in connection with German and Dutch art institutions. The Westfälischer Kunstverein was one of the project partners. plugin was funded by the EU and INTERREG partners under the umbrella of the INTERREG-programme.