Third Lung

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

02.02.-11.03.2018

Galerie im Turm

curated by Lena Johanna Reisner

How connected we are with everyone.

The space of everyone that has just been inside of everyone mixing

inside of everyone with nitrogen and oxygen and water vapor and

argon and carbon dioxide and suspended dust spores and bacteria

mixing inside of everyone with sulfur and sulfuric acid and

titanium and nickel and minute silicon particles from pulverized

glass and concrete.How lovely and how doomed this connection of everyone with

lungs.Juliana Spahr, 200111

Breathing is a vital function, a critical life process. It takes place continually, though it is usually subconscious. Concentrating on the breathing process forms a central component of mindfulness training, yoga, and meditation. It is a vehicle through which the mind may always find a way back to the body, and therefore into the here and now.

Breathing is an action of life itself, and is thus central to a large number of living beings, regardless of the organs they are equipped with. In traditional Chinese culture and in Taoism, Qi refers to a certain life energy flowing through everything. The direct translation of this is breath, air, or breeze. The same is true of the Hebrew word rûah, which originally means wind or breath, but is often interpreted as spirit. Atman, similar to the German word “Atmen” (breathing), is a key principle of ancient Indian philosophy, meaning essence or soul. Similar concepts are to be found across most world religions and cultures, where this vital activity – which more occurs within the subject than is actively practiced – is imbued with a transcendental dimension.

In the poem above, Juliana Spahr reflects on the interconnectedness of life forces through the function of the lung, an action characterised by ambivalence and fragility. In addition to listing particles found in the atmosphere, she writes of pulverised glass and concrete. These two materials bring to mind the September 11 attacks, after which the poem was written. Disaster, it seems, can be breathed. The sad truth of this statement resonates across the fields of war, at least since the deployment of poisonous gases in the First World War. Emissions, fossil fuels, and smog are their more civilian equivalents. While they develop into an acute problem in Chinese metropolises and elsewhere, we collectively face their longterm consequences with varying intensities of resistance.

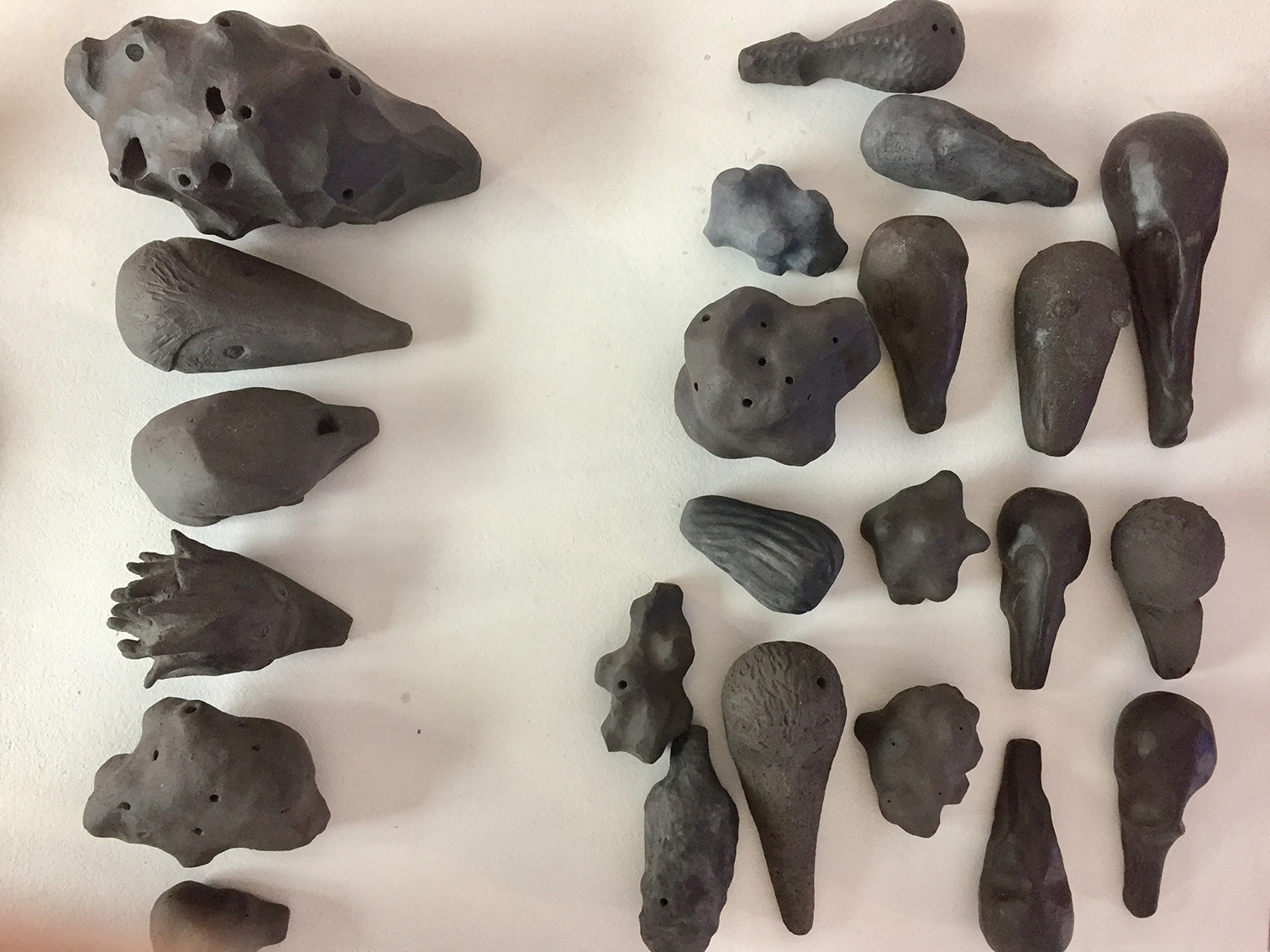

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, bird whistles as part of the multi-part installation Third Lung, 2017

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s multi-part installation Third Lung (2017) is inspired by the respiratory system of birds, which consists of a small lung with many, thin-walled appendages. The number of these so-called ‘air sacs’ varies according to species, and serves to increase oxygen intake during the intensive act of flying. With their ultra-light physique, sturdy torso and high-frequency heartbeat, the animals are perfectly geared towards the demands of flight. Although every act of singing is facilitated by specific breathing techniques, in birdsong, air sacs also affect the formation of voice, becoming a part of that persistent and varied musicality.

Third Lung (2017) arises in the context of a series of spiritistic séances, in which the artist connects with the souls of extinct species of bird. Responding to sounds detected by participants in previous séances, the artist has formed a series of clay bird whistles. Third Lung combines these whistles with four sculptures, forming a constellation that is to be activated through performance.2 Foregrounded by a concept connecting soul, breath, and voice, sound and musicality appear to be perfectly suited to communicate with a consciousness existing outside our reality.

The bird whistle has a long history as an instrument. In addition to flutes and ocarinas, which tend to have a rounder chamber, whistles were widely used across Mesoamerica, among other places. Like the far better-researched figurines of this cultural period, the wind instruments of the pre- and late classical eras have complex iconographies. Anthropomorphic, hybrid, and zoomorphic forms are common, although representations of birds occur particularly frequently.3 In the clay instruments of Third Lung, Ramírez-Figueroa has revisited this spectrum of forms.

These instruments are to be understood differently to the ordinary bird whistles familiar to us from ornithologists and bird-watchers. Indeed, in the case of Mesoamerican aerophones, music archaeologists assume mimetic aspects were key to their performative use. If, for example, tails are constructed as mouthpieces and the chamber as a body, with an outwardly facing head, then performance may well have involved both embodiment and transformation: a moment of ‘becoming the bird’, allowing the world to be seen from the perspective of an animal intimately linked to the cosmos. In the classical period in Oaxaca, Mexico, birds were viewed as messengers between spheres of existence.4

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa performing bird whistles as part of is work Third Lung at the 57. Venice Biennale 2017, photo: Stefan Benchoam, Courtesy the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta

Beloveds, we wake up in the morning to darkness and watch it

turn into lightness with hope.

Each morning we wait in our bed listening for the parrots and

their chattering.

Beloveds, the trees branch over our roof, over our bed, and so

realize that when I speak about the parrots I speak about love

and their green colors, love and their squawks, love and the

discord they bring to the calmness of morning, which is the

discord of waking.5

Today, birds and their songs continue to accompany humans. In rural and urban areas, and across geographies, the morning hours are filled with their lively activity. Juliana Spahr’s poetry contains a party subtle, partly forthright ambivalence – a depth that is also present in Ramírez-Figueroa’s work. For, despite the life- affirming connotations of breathing, death remains present in Third Lung. From its genesis in a series of spiritistic séances to communicate with the great beyond, to its hearkening back to bird species long extinct, there is something latently disturbing, but also touching, in the work. Extinction is an endpoint, strangely final. The Mesoamerican culture, too, belongs to the past – not only historically, but archaeologically. In drawing on such cultural techniques and myths, Ramírez-Figueroa opens a fissure to these pasts, finding in the contemporary, everyday, sometimes almost humorous and loving handling of materiality and iconography – a type of relief, perhaps.

- Spahr, Juliana (2001): Poem Written after September 11, 2001, in: Spahr, Juliana (2015): This Connection of Everyone with Lungs. Berkley / Los Angeles: University of California Press, p.8.

- The shape of the sculptures, perforated with wholes in which the instruments are nesting, furthermore recalls a 15,5 t heavy iron-nickel meteorite with characteristic cavities, found in the Willamette Valley in Oregon.

- See Hepp, Guy David / Barber, Sarah B. & Joyce, Arthur A. (2014): Communing with nature, the ancestors and the neighbors: Ancient ceramic musical instruments from coastal Oaxaca, Mexico. World Archaeology, 46:3, p. 380-399.

- See ibid.

- Spahr, Juliana (2002-03): Poem Written from November 30, 2002, to March 27, 2003, in: Spahr, Juliana (2005): This Connection of Everyone with Lungs. Berkley / Los Angeles: University of California Press, p.15.

Credits

Translation: Sonja Hornung

Copy editing: Richard Pettifer

Project assistant: Svenja Gründler

Third Lung was commisioned by La Biennale di Venezia, 2017.

Courtesy the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City

With the kind support of Senatskanzlei Kulturelle Angelegenheiten and Ausstellungsfonds Kommunale Galerien. Galerie im Turm is an organisation of the district office Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. The artist and the curator wish to thank the team of Galerie im Turm and Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, Stéphane Bauer, Sylvia Sadzinski, Theres Laux and Alice Royoux, the gallerist Stefan Benchoam, Jennifer De León and Dario Sevieri for their support with data management, KNM Campus-Ensemble under the direction of Rebecca Lenton with Christian Pokert and Ursula Praetor for their musical intervention, Nicolas Gomez and Kerstin Podbiel for their patience with installing the exhibition, Carsten Höland Elektrotechnik GmbH for their knowledgable advice, Giada Dalla Bontá for mediating the communication with La Biennale di Venezia, the registrar Sandra Montagner as well as Carolin Streller for her support.