Fossil Experience

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé, Monira Al Qadiri, Kat Austen, Marjolijn Dijkman, Rachel O’Reilly

with poetry by Róža Domašcyna, Ibiwari Ikiriko, and Julia Spicher Kasdorf, as well as further contributions from Christopher Basaldú, Caroline Breidenbach (wasserstories), Ayasha Guerin, Fossil Free Berlin, Fossil Free Culture NL, Rebecca Abena Kennedy-Asante (Black Earth Kollektiv), Klimaneustart Berlin, Anna Lena Kronsbein (Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries), Maike Majewski (Transition Town Pankow), Elske Rosenfeld, Liz Rosenfeld & Dasniya Sommer, Esteban Servat, Sumugan Sivanesan (Black Earth Kollektiv), The Driving Factor (Elisa Bertuzzo, Daniele Tognozzi, Neli Wagner), Wassertafel Berlin-Brandenburg (Heidemarie Schroeder), and Philine Wedell (Senate Department for Economics, Energy and Public Enterprises).

07/04–19/05/2022

An exhibition and program by Prater Galerie curated by Lena Johanna Reisner with curatorial advisor Sonja Hornung

VENUES:

Großer Wasserspeicher

Belforter Straße, 10405 Berlin

Kleiner Wasserspeicher

Diedenhofer Straße, 10405 Berlin

and Schankhalle Pfefferberg

Schönhauser Allee 175, 10119 Berlin

The exhibition Fossil Experience and its accompanying program addressed a number of the widely divergent – and in part violent – realities generated by the use of fossil fuels. The wealth accrued by specific social groups, nation states, and corporations by means of fossil fuels is inseparable from the ecological disasters at the sites where they are extracted, processed, and transported. In regions with high levels of energy consumption, including post-industrial urban centres such as Berlin, fossil energy and petroleum-based products are ubiquitous. A large part of electricity provision continues to be dependent on fossil infrastructure. At the same time, greenhouse gas emissions, toxic waste, and environmental damage arising from the production, transport, and burning of fossil fuels continue to be overlooked, or are downplayed by powerful institutions.

The notion of fossil experience points, on the one hand, to the experience of acceleration made possible by the widespread availability of cheap energy, particularly in the second half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, it refers to the traumas of extraction, exposure, and displacement, which threaten to further escalate as climate change progresses. The emphasis on the notion of “experience” underscores the fact that fossil energy and petrochemical products do not only exist “outside” of us or “elsewhere”: everybody has a fossil experience and in a global net of trade relations, resource extraction, production, and speculation, countless places and existences are connected to one another.

Fossil experience also bleeds into the long-awaited energy transition as, in the guise of a supposedly green capitalism, this transition is instrumentalised by a number of corporations to continue maximising profits. But it is neither sufficient nor acceptable to greenwash energy technologies that simply repeat dubious extractivist logics. Climate change and environmental devastation can only be addressed by centering demands for social and ecological justice, including environmental reparations.

Fossil Experience slowed down prevailing narratives about the energy transition, and investigated the legacy and scope of ongoing fossil fuel dependency. Located in a former water reservoir, the exhibition brought together artistic works and stories about geographies affected by the speculation and resource extraction involved in energy production. The exhibited works offered insight into the tight relationship between the capitalist growth imperative and ongoing colonial logics in relation to fossil energy sources. They focused on the wide-reaching consequences for interdependent human and more-than-human ecosystems, and acknowledged the political movements that advocate for their protection. Resonating with the former function of the site, the exhibition constantly returned to the threat posed by large-scale industrial projects to bodies of water.

Fossil Experience recognised that fossil infrastructures and energy politics continue to financially enrich specific social groups, nation-states, and companies. Concerned for the health of human and more-than-human ecosystems, the exhibition addressed experiences of violation and vulnerability caused by fossil realities which, if unchecked, will continue to call organised life on the planet into question. In doing so, the exhibition pointed towards aesthetic strategies in the representation of these realities as well as their possible undoing.

Download brochure:

EXHIBITION

23/04–08/05/2022

Großer Wasserspeicher

Belforter Straße, 10405 Berlin

Opened daily 12-8 pm, Thursdays 12–10 pm

22/04/2022, 6–10 pm

Exhibition opening

23/04 and 05/05, 4–5 pm

Guided tours with the curators in German language

24/04, 4–5 pm and 28/04, 7–8 pm

Guided tours with the curators in English language

Bilingual brochure Fossil Experience, centerfold with floorplan, graphic design by fertigdesign, photo: Lena Johanna Reisner

EXHIBITED WORKS

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé, Ogoni Cleanup, 2020, installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé

Ogoni Cleanup (2020)

Video performance, 2-channel video shown as split-screen, colour and sound, 3:44 minutes

In a 2020 performance, Ayọ̀ Akínwándé attempts to clean a river course in Ogoniland in the Niger Delta. The video documentation of Ogoni Cleanup shows how, with his bare hands, Akínwándé pushes water from one place to the other, adding clean water with a canister. Played in a loop, this activity seems to be both endless and futile.

In the Niger Delta, over half a century of oil extraction has left environmental damage on a gigantic scale in its wake, compromising the health and wellbeing of those who live there. In 1956, Royal Dutch Shell began extracting oil in the federal state of Bayelsa in the heart of the Niger Delta. From this point onwards, multiple national and international mineral companies have been active in the region. Oil pollution due to defective infrastructure, neglect of risk management procedures, and a lack of crisis intervention remain a constant problem. Humans, as well as more-than-human ecosystems, are significantly affected by the resulting environmental degradation, as well as air pollution and acid rain from the burning of expelled gases.

Akínwándé’s performance criticises the lack of efforts on the part of the government, as well as of international and national companies, in stopping oil pollution and cleaning local ecosystems. Leaks in infrastructure – which has in part already been shut down – often remain untreated for days or weeks, allowing crude oil to flow into water bodies, mangrove forests, and agricultural areas, while decimating fish populations and destroying harvests. People living in the Niger Delta are not only directly exposed to pollutants such as heavy metals and other components; their food security is also massively threatened.

In the title of the work, Ogoni Cleanup, which refers to the Niger Delta as Ogoniland, Akínwándé honours the presence of the Ogoni people, who have fought for decades for independence and against the destruction of their livelihoods. Founded in 1990, the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), led by Ken Saro-Wiwa, organised numerous protests, ultimately managing to push Shell to temporarily end its activities in Ogoniland. In the same year, the region was occupied by Nigerian military forces. Together with eight further fellow campaigners, Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed in 1995. Through their unyielding commitment, Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Ogoni Nine, and MOSOP have set an international example of resistance against the oil industry. At the same time, the case makes transparent the extent of violence to which nation-states and companies – in this case Royal Dutch Shell – are willing to resort in the Global South, while underscoring the level of danger to which activists in the Global South continue to be exposed.

Monira Al Qadiri

Wonder 1, 2, 3 (2016–2018)

Three natural pearls (each 1 cm) in aquariums, dimensions variable

Kuwaiti artist Monira Al Qadiri’s Wonder 1, 2 and 3 display natural pearls that have been carved into the form of oil drill heads. In the Gulf region, pearl diving has a long tradition that has shaped the region’s economy and played a central role in cultural life. Archaeological finds from the Arabian peninsula demonstrate that natural pearls were already extracted in the late Stone Age (6000–5000 BCE). With their iridescent glow, they were the inspiration for countless legends, and have been attributed with many different meanings by various cultural groups around the world. Today, they continue to be appreciated as jewellery pieces. Natural pearls symbolically evoke a range of attributes, from purity, wisdom, and fertility, to tears of sadness.

Well into the 1930s, more than 100,000 workers would travel to the inland sea to work during the season from April to September. These workers included enslaved people from the African continent, contract workers, and professional divers from Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar. At great risk, they would dive more than 30 times per day in order to gather natural pearls from the oyster-rich banks. The discovery of oil meant that pearl diving was no longer economically significant from the mid-20th century, when in many Gulf states, including Kuwait, the export of crude oil became a key source of income.

By aligning two motifs – natural pearls and the drill heads used to extract oil – Al Qadiri connects two different phases in the cultural and economic histories of the Gulf. Both oil drilling and pearl diving extract organic materials considered to be of value from below the surface. However, the global power relations and environmental conditions that brought these extractivist practices to the fore differ. Al Qadiri’s work raises questions relating to the representation of continuities and breaks in the region and in particular in Kuwait, which was laid to waste when withdrawing Iraqi troops set fire to oil fields at the end of the Gulf War in 1991. Wonder is also embedded in Al Qadiri’s personal history, as her grandfather was a singer on pearl diving boats. Placed in artificially decorated aquariums, the drill-shaped pearls represent the distortion of historical narratives caused by the industrial reverberations of a single substance. In this way, petromodernity can be seen to mutate both cultural practices and the lens through which they are viewed.

Monira Al Qadiri, Wonder 1, 2, and 3, 2016-2018 (detail), installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

Kat Austen, This Land is Not Mine, 2020–2022 (detail), installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

Kat Austen

This Land is Not Mine (2020–2022)

20-channel video installation with soundscape, 14 minutes

Kat Austen’s multimedia project investigates Lusatia, a region that extends from the German federal states of Sachsen and Brandenburg to the voivodeships of Lower Silesia and Lubuskie in West Poland. Since the 1890s, the development of Lusatia’s economy and landscape has been determined by resource extraction. According to the Archive of Disappeared Places (Archiv verschwundener Orte), due to the expansion of the lignite (brown coal) industry, since 1924, a total of 137 places have been relocated and replaced with open cut mines and industrial infrastructure. Lignite, however, has led not only to loss. It has also created jobs in the region, and then as now, it has contributed to narratives about Lusatia’s identity. However, multiple identities coexist in Lusatia, and their histories predate current national borders.

This Land is Not Mine addresses these coexisting identities in Lusatia – which is home to the Sorbian cultural group and a plethora of further human and non-human beings – as it undergoes fundamental socio-economic transformation as a result of the phaseout of lignite-related industries. Consisting of twenty small-format screens, Austen’s audio-visual installation displays a series of vignettes registering impressions of Lusatia recorded by the artist over two years. The accompanying sound composition is comprised of field recordings gathered both by the artist and by those living in Lusatia, uploaded to the online platform Lausitzklang, which was specifically built for This Land is Not Mine.

The title of the work, This Land is Not Mine, incorporates a play on words in which multiple layers of the work begin to unfold. On the one hand, “the mine” as a site of extraction points to the fact that there are facets of Lusatia beyond the coal industry. There are countless further narratives that characterise the region, which shift and come to light as industry in the region undergoes rapid transition. On the other hand, the reference to “mine” as a possessive pronoun raises questions around property and land ownership, both in the sense of belonging and in relation to access rights. Are property relations, which in practice allow for human dominance over land and ecosystems, at all reconcilable with fundamental principles of sustainability? The title This Land is Not Mine also refers to the artist’s personal relationship to the region. Austen, who grew up close to the Welsh border in Great Britain, moves through Lusatia as a visitor. She encounters a landscape to which she does not belong – but where much is familiar.

The project This Land is Not Mine was funded by the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS), Potsdam, as part of an artistic research grant. The 20-channel video has been realised with help by Kazik Pagoda, aBe Pazos, and Will Greensmith. Sound recordings were contributed by Ili Os, Christina Kliem, Johannes Staemmler, John Grznich, Erik Lemke, and Martin Ballaschk.

Kat Austen

Stranger to the Trees (2020)

Glass sculpture with fluorescent liquid and microplastic, metal frame, 2-channel video installation with colour and interactive sound (7 minutes), cotton fabrics, online exhibition via post-gallery.online

In the interdisciplinary project Stranger to the Trees, Kat Austen investigates the implications of the spread of microplastics for forest ecosystems. Due to the durability of petrochemical plastics, it is expected that they will accumulate and remain in the environment in the long term.

Early research on the influence of microplastics on the environment has mostly focused on their distribution in water ecosystems and their interaction with aquatic flora and fauna. In the ground, microplastics are less conspicuous, but their concentration is many times higher and accumulates both through direct entry and via atmospheric deposits. Austen’s multimedia installation Stranger to the Trees addresses possibilities of complementarity by asking how microplastic and trees in forest ecosystems might coexist.

Alongside field recordings and artistic research in birch groves between Berlin and Wrocław, Austen also cultivated birch trees in contact with microplastics, teaching herself the Renaissance piccolo by serenading the birches daily. Using DIY methods derived from scientific literature, Austen marked microplastic beads (5-50 μm) with a fluorescent pigment and introduced them into the ground of potted silver birches during their growth period. After five months, the root samples were examined using fluorescence and confocal laser scanning microscopy. In this way, indications of microplastics in the trees’ root structures could be documented and new insights gained relating to the phytoremediation potential of silver birches – that is, their ability to contribute to the decontamination of soils with elevated levels of microplasticsby uptake through their root system. The outcome of this work encompasses the Stranger to the Trees installation, as well as a peer-reviewed academic article demonstrating the removal of microplastic from the soil via birch tree roots.1

As a multimedia installation, Stranger to the Trees brings together an interactive soundscape with moving images of microscopic close-ups and birch forests. Contained by a glass sculpture shaped in the form of a birch, fluorescent liquid reflects the medium used in the research process.

Stranger to the Trees was realised within the framework of the European Media Art Platforms EMARE program at WRO Art Center with support of the Creative Europe Culture Programme of the European Union. Consulted experts: Joana McLean, Franz Hölker, Daniel Balanzategui, Simon Barraclough, Pawel Janicki, Kamila Mróz, and Michal Adamski. Special thanks to: Matthias Strau., Bernhard Bosecker, Kristen Rästas, Kelli Gedvil, Andreas Baudisch.

- Austen et al. (2022) „Microplastic inclusion in birch tree roots“, Science of the Total Environment, 808, 152085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152085

Kat Austen, Stranger to the Trees, 2020, installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

Marjolijn Dijkman, Cloud to Ground #1, detail, 2021, installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

Marjolijn Dijkman

Cloud to Ground #1 (2021–2022)

Floor installation with fulgurites (produced with sand from Genk (BE), Lommel (BE) and Manono (DRC), copper powder, cassiterite, lithium) and loose sand from Lommel (BE), dimensions variable

For her series Cloud to Ground, Marjolijn Dijkman has created artificial fulgurites by running electricity through sand and earth. These materials were acquired from sites where raw materials are extracted in Belgium and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Fulgurites form naturally when lightning hits the ground, where it can discharge up to 100 million volts in a split second. The heat released causes sand, rock, organic deposits and other sediments to fuse, or vitrify. The clumps and tube-like artefacts that form in the process are also known as “fossilised lightning”.

Cloud to Ground #1 arose as part of Dijkman’s research on the history of electricity and a series of experiments to render electric charges visible using various materials. In Cloud to Ground, Dijkman references the moment in Western European 18thcentury scientific research in which electricity began to be investigated as a natural phenomenon, and then systematically put to use. Whilst in contemporary living environments, electricity production often takes place out of sight and is generally taken for granted, during the Enlightenment in the 18th century, electric phenomena were often demonstrated in order to educate and entertain.

Some of the material vitrified in the fulgurites comes from Genk, a former coalfield in the Belgian province of Limburg. Coal was discovered in the area at the start of the 20th century and extracted from 1914 to 1988 in the Winterslag coal mine. In a Western European context, structural change in energy provision already began as early as the 1960s. Today, there is broad agreement that the full phase-out of coal-fired energy production must take place as soon as possible, as other technologies for generating and storing energy are put forward.

In this sense, the electrification of transport is a central factor in the energy transition. For this, battery technologies currently rely on lithium, a light alloy that is the object of increasing financial speculation. This means that resource extraction continues unabated in other places, for example in Manono in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a former Belgian colony where tin was mined from 1919 until 1982. In Cloud to Ground #1 Dijkman has also used sand from Manono. Currently, one of the largest lithium rock mines is being developed there by Austrian and Chinese companies. Through this, the material composition of the fulgurites raises questions relating to resource extraction, financial speculation, and electrical technologies in light of ongoing asymmetries in global power relations.

Rachel O’Reilly

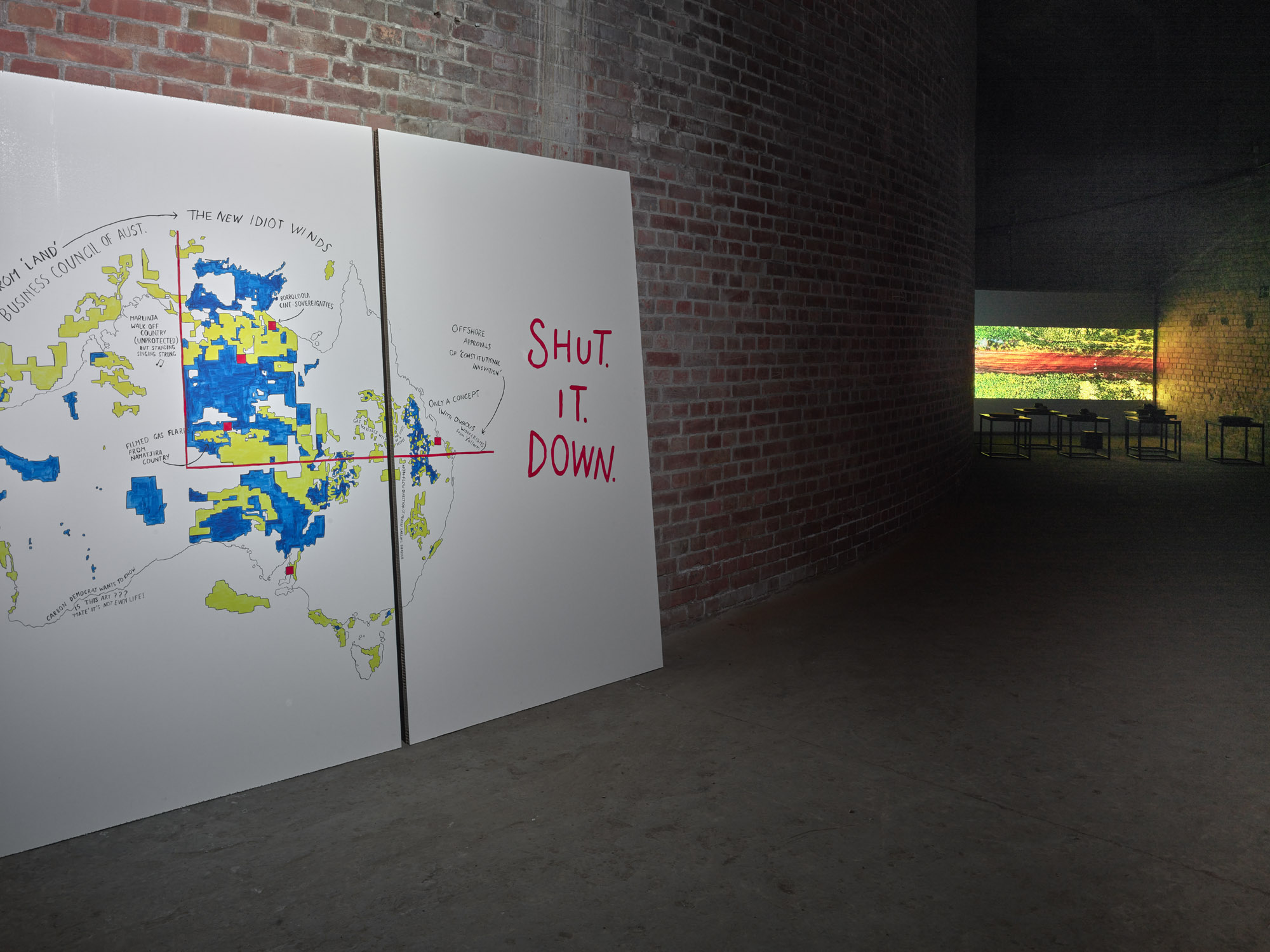

INFRACTIONS (2019)

Documentary, split screen, colour and sound, 60 minutes, thematic map

INFRACTIONS is a feature length video installation platforming frontline Indigenous artist and cultural workers’ struggles against threats to more than 50% of the Northern Territory of Australia from shale gas fracking. As the country becomes a leading exporter of planet-warming fossil gas globally, pressure on this region has intensified, threatening hard-won Aboriginal land rights and homelands.

Plans to ‘Develop the North’ of Australia have been resurrected at different moments since the nineteenth century, but abandoned just as quickly for being built on fantasies that related little to the actual behaviour of monsoonal-desert water systems. With the lifting of a state moratorium in 2018, British, US, and homegrown mining companies seek to roll out toxic drilling rigs over vast underground flows, which are key connecting sites of culture, law and food for First Nations.

Refuting capitalist and colonial models of land and water in the driest continent on earth, INFRACTIONS features musician/community leader Dimakarri ‘Ray’ Dixon (Mudburra); two-time Telstra Award finalist Jack Green, also winner of the the 2015 Peter Rawlinson Conservation Award (Garawa, Gudanji); musician/community leader Gadrian Hoosan (Garrwa, Yanyuwa); ranger Robert O’Keefe (Wambaya), educators Juliri Ingra and Neola Savage (Gooreng Gooreng); Ntaria community worker and law student Que Kenny (Western Arrarnta); musician Cassie Williams (Western Arrarnta); the Sandridge Band from Borroloola; and Professor Irene Watson (Tanganekald, Meintangk Bunganditj) contributor to the draft UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 1990–1994.

As the camera connects incommensurable legal geographies, extractive industry and labour history to ongoing resistances and movement, defenders of culture and water warn of stories of manufactured consent, and Indigenous legal theorist Irene Watson explains the limits of the Western international legal system for planetary survival and justice.

Director/Research/Camera/Sound: Rachel O’Reilly

Producer: Mason Leaver-Yap

Editor/Visual Research: Sebastian Bodirsky

Camera: Tibor Hegedis, Colleen Raven (Nharla Photography)

Sound mastering: Jochen Jezussek

Map visuals: Valle Medina, Benjamin Reynolds (Pa.LaC.E)

Subtitles: Sebastian Bodirsky, Katharina Habibi, Sonja Hornung

Rachel O'Reilly, INFRACTIONS, 2019, installation view Fossil Experience, Prater Galerie hosted by Großer Wasserspeicher, 2022, photo: Eric Tschernow

TEAM

CURATION: Lena Johanna Reisner

CURATORIAL ADVISOR: Sonja Hornung

TEXTS: the curators, artists, and poets

TRANSLATIONS AND EDITING: Gegensatz, Bradley Schmidt, and Anna Förster

GRAPHIC DESIGN: fertigdesign

PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS: Carola Uehlken

PRODUCTION: Carolina Redondo

TECHNICAL TEAM: Claudio Aguirre, Carlos Busquets, Marcos Mangani, Nicolas Matzner, Alberto Sardo, and Studio Kat Austen

TEAM PRATER GALERIE: Katharina von Hagenow, Lena Prents, and Julie Rüter

Thanks to Stefan Bienas, Sebastian Bodirsky, Haus für Poesie, Uli Huemer, Aleksandra Jach, Alexander Klose, Antje Majewski, Sybille Neumeyer, Lee Plested, Steve Shaba (Kraft Books), Anne Szefer-Karlsen, and Kunle Tejuoso (The Jazz Hole).

Fossil Experience was supported by Stiftung Kunstfonds, LOTTO-Stiftung Berlin, and the Senate Department for Culture and Europe, kindly supported by Förderband Kulturinitiative Berlin and Schankhalle Pfefferberg. The presentation of Stranger to the Trees by Kat Austen in cooperation with postgallery.online was supported by Neustart Kultur. Media partners: Berlin Art Link, taz.